In Praise of Ear Learning

December 1, 2021 on 4:57 pm by Michael Grey | In Solo Piping | Comments Off on In Praise of Ear LearningIt dawned on me as I waded through the day’s Duolingo French exercises: learning a language is easiest by immersion; that is, to be constantly around the sounds of the language. To live it, to learn what the sounds mean, what they represent. In childhood, for instance, I’d have to think it’s often the things done wrong that prove to be the speediest way to ingrain words. As goes the old axiom: we most often learn best from the mistakes we make: “Mon Dieu! Idiot! Le poêle est chaud ! Tu t’es brûlé la main !”.

Yes, I know; a gift of earth-shattering wisdom from the Mount this day. A hot stove may burn your hand. That and we learn our first language – we learn to speak – before we learn to read or write. Indeed, we learn one of the most monumental of life-skills by ear. Most of us learn to read and write years after language basics are instilled; years before the alphabet, grammar rules and how to move a pencil on a page.

And so, it’s interesting to me to think about how a lot of music is taught today. I suggest that in most places of musical learning (beyond, say, the Suzuki Method) the act of making music – those human movements needed to create an in-tune sound – is taught in tandem with the theoretical: staves, keys, bar lines, notes, scales, these kinds of things.

The most storied makers of music in piping never bothered with music theory. For instance, consider the MacCrimmon line of pipers. We know generations of this family of master musicians, many the inventors – and genius – at the core of our repertoire’s best compositions wouldn’t know a staff from a cromach. But they knew music. These great pipers were aware of arpeggios, tonal motifs, chord progressions, melodic symmetry and the secrets of compound, simple and irregular time. The evidence is there in the compositions they have left for the ages. Just don’t jump in your time machine to ask Donald Mor MacCrimmon for his score of A Flame of Wrath for Squinting Patrick. You’d get a squint alright – and no manuscript page.

Of course, the music of the Great Highland Bagpipe survives in no small part due to the aural tradition from which it springs. Until Joseph MacDonald starting placing our tunes on five straight lines in 1760 our music passed from teacher to student in words and song alone. In fact, the great music of the Great Highland Bagpipes survives because of dedicated ear learners. It feels, in a way, that pipers have spent the last two centuries playing catch-up to conventional music theory, the lingua franca of the broader world of music-making. Our grand ear-learning history has engendered a sort of blanket pipers’ insecurity – at least when it comes to the big world of music.

I often think it feels like we move too quickly to tamp down the ear-learning virtuosity of those that came before. I can think of not a few gold medallists, big prize-winners – including championship-winning drummers – who scored their greatest tunes while unable to reliably score a page of music.

And what of greats of the much wider world of popular music? It’s hard to imagine that great composers like Bob Dylan, Irving Berlin, Michael Jackson and all four members of The Beatles lacked proficiency in reading and scoring music. Said John Lennon in a 1980 interview, “None of us could read music … None of us can write it. But as pure musicians, as inspired humans to make the noise, they [band members] are as good as anybody.”

Exceptional examples of ear-learners aside, are there benefits to ear-learning? One is the a tighter connection of what the ear hears and the sound the instrument produces (versus what the eye sees). When the focus is on eye-to-music-making the ear is easily overlooked. The ability to hone pitch recognition is lost. Easy pitch recognition is a boon to anyone finding their way in collaborative studio work arrangements – or any situation where they make music on the fly with others. Or, learning music without a printed score.

It seems to me, too, a reliable and practiced musical ear will better inform creative music-building. With no visual constructs and boundaries – the kind of set-up our MacCrimmons enjoyed – creativity is unbridled. The musician’s focus is entirely on sound, on music-making. Said Taylor Swift, one of the pop music world’s most successful song-writers, “I would not have majored in music because when music becomes technical for me I don’t like that part of it.”

I used to be of the mind that believed people who took up the instrument had to start with exercises and scales and tunes that were of the instrument (think the old College of Piping “green book” – my first tutor manual): a person’s first tune must be of the widely-accepted piping “tune book”. I worry now if that approach is still effective. Increasingly, I find myself of the mind that we must do whatever it takes to get chanters and sticks in the hands of new aspirants. At least, that is my view from my perch here in Ontario. We have to keep working to make it easy; fun, too – likely with some connection to the real world of a learner. The heavy anthemic tones of “Scot’s Wha’ Ha’e” aren’t likely all that alluring to an inner-city kid in Canada – or anywhere, for that matter. Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off” on the practice chanter? I could live with it if we hooked more to take up and stay with the instrument. Any pop start might be augmented by the best of the tradition in due course.

There’s so much that is great about the music of the Great Highland Bagpipe. I wonder if we embraced ear-learning a little more, focused first on creating an environment that nurtures a long and abiding love for the music (I know this is already happening in places around the world). Any effort of this kind can easily be followed on by the theoretical.

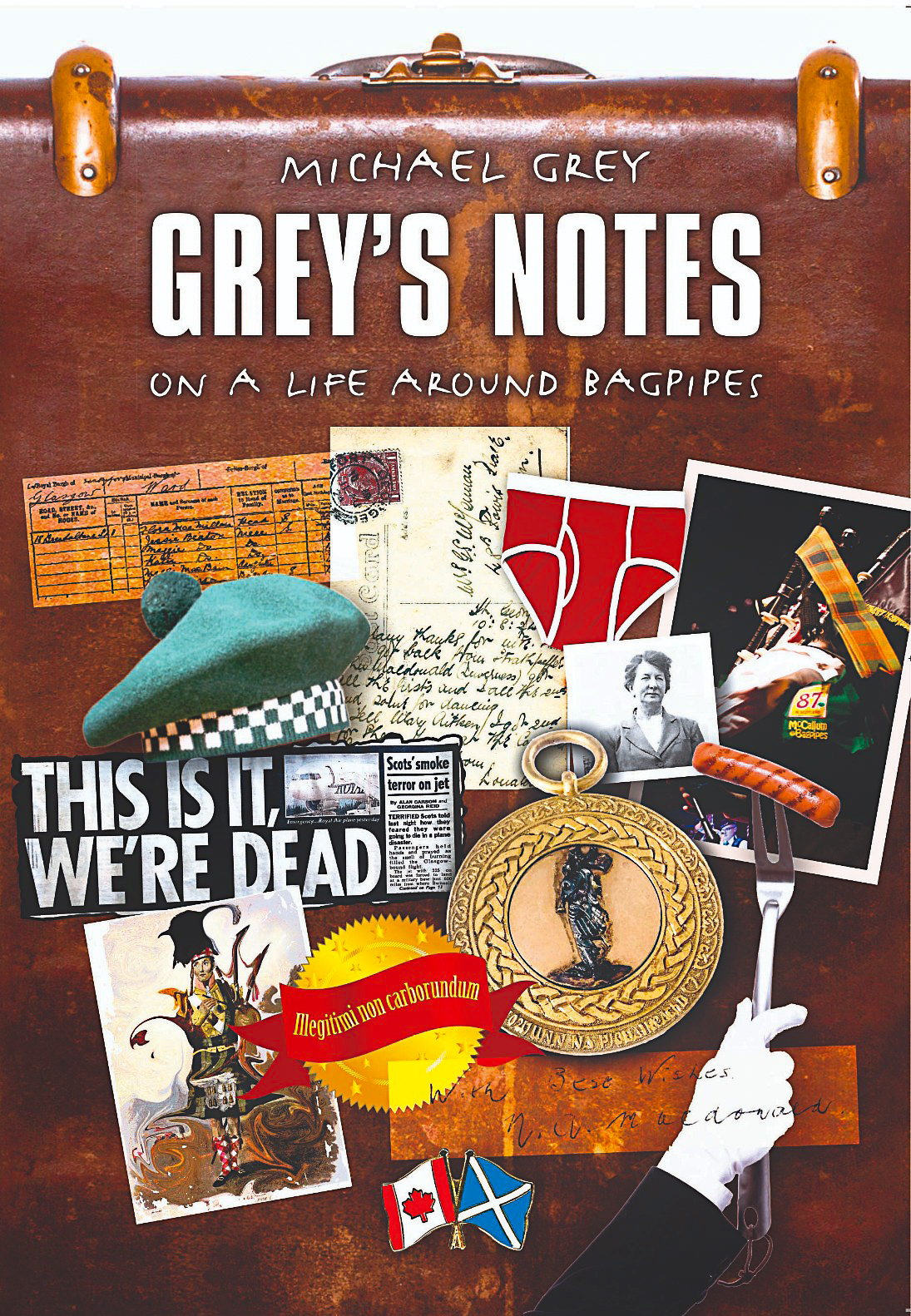

After all, I have seven books of printed music to shill!

M.

No Comments yet

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Dunaber is using WordPress customized and designed by Yoann Le Goff from A Eneb Productions.

Entries and comments

feeds.

Valid XHTML and CSS.

Entries and comments

feeds.

Valid XHTML and CSS.